Resistance to Diversity and Inclusion Change Initiatives: Strategies for Transformational Leaders

Rapidly shifting U.S. demographics are causing organizations to encounter increased demand to build culturally competent, inclusive workforces.

Share This Post

Maria Velasco, MA

Fielding Graduate University, USA

Chris Sansone, PhD

Fielding Graduate University, USA

Maria Velasco, MA has over 15 years experience consulting for organizations seeking transformational

Maria Velasco, MA has over 15 years experience consulting for organizations seeking transformational

change in the area of diversity and inclusion. She develops and implements sustainable initiatives to help strengthen and leverage diversity for

organizations from a variety of sectors. Maria uses Appreciative Inquiry and Action Learning methodologies to build cultures of inclusion and to foster intercultural understanding. She has a Masters Degree in Organizational Development and Leadership from Fielding Graduate University.

Author’s

Contact Information:

Maria Velasco, MA

Phone: 360-789-6037

Chris Sansone, PhD has over 20-years experience designing leadership programs and change initiatives emphasizing mind, emotion and spirit in scientific, technological, university and engineering

Chris Sansone, PhD has over 20-years experience designing leadership programs and change initiatives emphasizing mind, emotion and spirit in scientific, technological, university and engineering

organizations. A Prosci Change Practitioner he helps his clients and builds workforces of change readiness and inclusivity. Certified by the Coaches Training Institute, Chris’s doctorate is in Organization Development from the Fielding Graduate University and teaches at the Hoffman Institute.

Author’s

Contact Information:

Chris Sansone, PhD

Phone: 720-938-3036

Principal

Verticle Leadership

2030 Oak Avenue

Boulder, Colorado 80304

Abstract

Rapidly shifting U.S. demographics are causing organizations to encounter increased demand to build culturally competent, inclusive workforces. Review of current literature and the authors’ primary research suggests broad attitudinal and ideological shifts concerning the role of resistance in diversity and inclusion initiatives especially as it concerns responsibilities of transformational leaders. An alternative orientation around resistance is presented along with effective strategies for transformational leaders to anticipate, address and redirect fear-based behaviors in order to succeed in diversity and inclusion change initiatives.

Keywords: Leadership, diversity, change, equity, training, culture, and strategy

Race and gender disparities raise sensitive issues, consequently diversity and inclusion change initiatives often trigger unique reactions, behaviors and emotions, for and against (Gonzalez, 2010). Paradoxically, individual, group, and organizational resistance rather than being an obstacle may serve a critical role assuring change success.

The United States’ workplace is undergoing rapid demographic change. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, over the next four years members of the Asian labor force is projected to more than double and Hispanics will account for about 80% of the total growth of the U.S. labor force. Growth of Black Americans to 2050 is projected to be 6.4 million. The White labor force is declining in comparison to those of other racial and ethnic groups (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015).

Companies with greater workforce diversity and inclusion have higher profits and increased innovation compared to those with a homogeneous workforce (Herring, 2009; Forbes, 2011; McKinsey, 2015). Regardless, organizations continue experiencing difficulties building inclusive cultures. Garr (2014) surveyed 250 North American companies and found that 71% aspire to have an inclusive culture where employees feel involved, respected and valued. However, only 11% reported having one in place.

While resistance in change management has been the focus of many studies (Coetsee, 1999; Hultman, 2003; Ford & Ford, 2008; Ford & Ford, 2009; Maurer, 1996; Piderit, 2000; Simoes and Esposito, 2014; Muo, 2014) little research has been done about the unique challenges and kinds of resistance encountered by transformational leaders in diversity and inclusion change initiatives. Our review of current literature and our own qualitative investigation reveals ways in which transformational leaders deploy resistance as a catalyst for change. Organization resistance is an employee’s dispositional inclination to contest new developments (Oreg, 2003). “Resistance can be contrasted with readiness, which is a state of mind reflecting willingness or receptiveness to change” (Hultman, 2003; p. 1).

We review literature on diversity and inclusion including an historical review of workplace inequalities and discrimination reform efforts, disadvantages of mandatory programs, and effective transformational leadership strategies for assuring change success.

Workplace inequality

People of color encounter a “glass-ceiling” to top levels of management hierarchies (Powell & Butterfield, 1997) and to asserting organizational influence (Block, 2014). In the U.S., companies with 100 or more employees the proportion of Black men in management between 1985 and 2014 increased marginally .3%, from 3.0% to 3.3%. Women in management rose from 22% to 29% between 1985 to 2000; however, have since experienced little increase (Dobbin & Kalev, 2016). Fortune 500 companies continue to be dominated by Whites, who represent 90.3% of corporate board memberships, with African Americans only 4.6%, Hispanics 3.0% and, Asian Americans, despite success in other job statistical outcomes, only 2.1% (Alliance for Board Diversity, 2011).

Research on organizational power status and influence indicates that “persons in low-status social groups are evaluated as less effective when in powerful positions, have their power viewed as illegitimate, use it more to show that they have it and suffer status loss from the use of power” (Lucas and

Baxter, 2012, p. 65). Additionally, institutionalized organizational practices and norms are guided by “racialized” assumptions that create lower expectations for workers of color and maintain racial hierarchies by their performing tasks deemed least desirable. While workers of all races may perform least desirable tasks, minority employees perform them at greater frequency, casting them in a light where they must work harder to reach more desired ideological, institutional, and physical norms typically ascribed to more privileged White

employees (Wingfield & Alston, 2014).

Discrimination reform

Antidiscrimination legislation and subsequent corresponding compliance diversity practices have helped increase workplace diversity, to a limited extent. Antidiscrimination diversity legislation was introduced in the U.S. in 1960. In 1965 Congress created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to enforce provisions of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 for eliminating discrimination in employment based on race, color, age, sex, national origin, religion, or mental or physical disability. Affirmative action programs originated by executive order in 1961 and later strengthened by executive order required government employers to take “affirmative action” to “hire without regard to race, religion and national origin” (Stephanopoulos & Edley, 1995). In 1967, gender was added to the anti-discrimination list. Title VII lawsuits and affirmative action’s compliance reviews have led to increases in women’s and minorities’ share of management positions (Dobbin, Kalev & Kelly, 2007). At the onset of Title VII the main goals of the majority of organizations’ diversity management training programs and policies included the avoidance of discriminatory employment practices and costly EEOC claims. Eventually emphasis would be placed on diversity as a business advantage.

Downside of compliance

While governmental reform efforts have led to increases in numbers of minority and women managers, organizations would encounter new areas of concern. “By the late 1970s and into the 1980s there was growing recognition within the private sector that these legal mandates although necessary, were insufficient to effectively manage organizational diversity. Many companies and consulting firms soon began offering training programs aimed at valuing diversity” (Herring, 2009, p. 209). A study of private-sector organizations

from 1971 to 2006 showed that implementation of mandatory diversity trainings have been insufficient at increasing the share of White women, Black women and Black men in positions of management due largely to employees’ disengagement in such efforts (Dobbin, Kalev & Kelly, 2007). Mandatory training programs have often posed adverse effects (Cavaleros, 2002; Lucas & Baxter, 2012). Attempts to control managers’ behavior and reduce biases resulting in greater propensity for resistance by Whites (Dobbin & Kalev, 2016). A study on diversity training programs spanning 31 years surveying 833 mid-size to large U.S. companies showed that mandatory diversity training programs, with an eye on avoiding liability in discrimination lawsuits, backfire. Black female managers dropped 10%, Black men in top positions fell by 12% with similar effects for Latinos and Asians. There was a 7.5% drop in the number of women in management overall. White males reported feelings of exclusion. In contrast, the most successful approach for increasing engagement across all groups was cross-functional teamwork. “People collaborate and cooperate rather than give and accept assignments. Previously invisible and undervalued workers voice their opinions on important issues or perform tasks no one thought they could. New types of relations between advantaged and disadvantaged groups are more likely to evolve under these conditions” (Kalev, 2009).

The Business Case for Diversity

“Organizations that want to remain competitive must be knowledgeable about the diversity that is present in the current workforce and marketplace if they hope to have a sustainable business” (Prieto, Norman, Simone, Phipps & Chenault, 2016, p.37). Data from 506 U.S. for profit business organizations positively links racial and gender diversity to several key business success outcomes including profits, earnings and market share (Herring, 2009), an affirmation of diversity as “a strategic resource that can be utilized to enhance organizational performance” (Jackson & Joshi, 2011, p. 651).

Power Dynamics

Sustaining equality is problematic due to “the entrenched economic interests, the legitimacy of class interests, and allegiances to gendered and racialized identities and advantages” (Acker, 2006, p. 460). Hindrances to equality refer to the power of managerial class interests outweighing the interests of the minority group. Thus, incumbent majority managers play a particularly important role in transforming their workplaces and their communities at-large, by inspiring inclusivity (Mor Barak, 2015). Leaders must re-examine and unravel unproductive power structures and attend to the ways in which structures reproduce inequalities (Ghorashi & Sabelis, 2013; Holck, 2016) and, moreover, assure equality of power, influence and access to resources to advantage the whole organization (Gonzalez, 2010).

Approaches That Work

Establishing organizational responsibility and encouraging managers’ involvement have proven to be effective in increasing the share of White women, Black women, and Black men in management. According to a 2016 study involving 839 U.S. firms, voluntary approaches to training have resulted in increases of 9.0% to 13.0% in Black men, Hispanic men, and Asian American men and women in positions of management over a period of five years, with no decline in White or Black women in managerial ranks (Dobbin & Kalev, 2016). Similarly, engaging all managers in recruitment and mentoring programs increases their support for organizational diversity (Jansen, Otten, & van der Zee, 2015; Jackson & Joshi, 2011). Mentoring programs (Dobbin, Kalev & Kelly, 2007) and assigning responsibility for diversity to a diversity manager or a task force of managers from different departments have proven successful (Dobbin & Kalev, 2016). Diversity committees have raised the proportion of Black women in management by 30%. Appointing a full-time diversity staffer raises the proportion of Black men by a healthy 14% (Kalev, Dobbin & Kelly, 2006).

Sources of Resistance

Some authors posit that employee resistance to change is negative and undesirable, to be opposed and ultimately overcome (Lewin, 1947; Dent & Goldberg, 1999; Merron 1993; Coetsee, 1999). Others view it as an important and necessary lever for change (Ford et al., 2008; Ford et al., 2009; Maurer, 1996; Piderit, 2000; Simoes & Esposito, 2014; Muo, 2014; Hultman, 2003). “Unfortunately, the word resistance often has a negative connotation. This is a misconception. Sometimesresistance isthe most effective response. If people’s beliefs, values and behaviors provide them with constructive ways of meeting needs, then it’s adaptive and healthy to hold onto them, and resist change” (Hultman, 2003, p. 4). Employees oppose change out of fear of the unknown, uncertainty and failure to be considered or informed (Muo, 2014) generating perceptions of potential loss or instability (Prediscan and Braduanu, 2012; Williams, 2009; Nesterkin, 2012; Maurer, 1996; Lewin, 1947). Opposition varies depending on levels of perceived anticipated negative effects (Prediscan and Braduanu, 2012; Nesterkin, 2012, Muo, 2014) including loss of job, position, income, power, authority, and economic insecurity (Muo, 2014). It is not surprising that opposition to change comes predominately from employees most directly affected.

Frequency matters. “Organizational change initiatives, which are often continuous, will undermine employees’ certain freedoms and volitions, which will arouse negative affective states” (Nesterkin, 2012, p. 589). Perceptions of fairness and equitableness or, the “perceived justice of change,” influence levels of resistance (Smollan, 2006). Anxiety is the affect most often associated with change (Nesterkin, 2012) posing additional resistance to be reckoned with. “The change process starts with disconfirmation, which produces survival anxiety and guilt–the feeling that we must change—but the learning anxiety associated with having to change our competencies, our role for power position, our identity elements, and possibly our group membership causes denial and resistance to change” (Schein, 2010, p. 313).

Ironically, change agents themselves can impede an initiative when lacking ownership and doubt its efficacy. Resistant behaviors include inappropriate communication, misrepresentation, refusal to accommodate requests and inquiries and acting with ambivalence or misleading employees regarding the effects of the change (Prediscan and Braduanu, 2012; Ford et al., 2008).

Resistance as a resource. Resistance rather than a barrier to be overcome, paradoxically, provides a gateway to change (Ford et al., 2008; Ford et al., 2009; Maurer, 1996; Piderit, 2000; Simoes & Esposito, 2014; Muo, 2014). Embracing resistance raises the likelihood of success by offering the opportunity to increase awareness for the need to change, build momentum and eliminate unnecessary, impractical or counterproductive elements in the design or conduct of the change process (Ford et al., 2008). Re-conceptualizing resistance and inviting ambivalence (Piderit, 2000) and similarly, embracing accompanying uncertainty, (Clampitt, et al., 2001) creates an organizational climate that reduces anxiety, increases courage and invites dialogue fostering creative change competencies. Fundamentally, action requires reaction for momentum to occur. These are interdependencies, inextricably linked. As they are a polarity, action is the positive pole and resistance is the negative pole. Attending purposefully to both is required for change. Where there is no resistance, change is impossible. Without resistance birds could not fly, fish could not swim and people could not walk.

Strategies for working with resistance. Strategies most effective for working with resistance take an “all-inclusive multicultural approach towards diversity” (Jansen et al., 2015) where concerns of all members, minority and majority, receive attention. Employee opposition can be potentiated or reduced, depending on management and leadership styles, communications, structure, organizational culture and others forces (Prediscan & Braduanu, 2012). Communication is an essential component for endorsing and assuring successful change (Simoes & Esposito, 2014). Transformational leaders benefit change by encouraging and supporting the voices of others through facilitation and formalized structures that inspire reflection and encourage organizational learning (Gonzalez, 2010).

Block (2014) recommends cultivating awareness of each member’s role and their contribution within diversity dynamics. “The first step in addressing diversity is an analysis of the self. Individuals need to be aware of personal patterns (personal attitudes and opinions), and have an understanding of interpersonal and cultural patterns. It is this self-knowledge that allows people to be non- judgmental and open” (Cavaleros et al., 2002, p. 52). Whites working in Human Resource Development (HRD) become more effective at understanding and managing diversity by working against the grain of their own White conditioning (Prieto et al., 2016; Monaghan, 2010). They do so by focusing on: 1) individual personal development for racial identity and White privilege recognition; 2) improving HRD functions of training, performance, assessment and career development; and, 3) becoming a role model vocalizing issues about racism and White privilege (Monaghan, 2010).

Practices associated with successful change efforts led by Chief of Diversity and Inclusion Officers (CDIOs) entail creating a diversity plan, building systems of accountability, using informed search processes, facilitating professional development and trainings, providing incentives (Williams and Wade-Golden, 2013), engaging managers and promoting social accountability (Dobbin and Kalev, 2016).

Without the support of White males organizations will fail to navigate change required to create diverse workforces. White males comprise about one-third of U.S. workers in private industry and at 62% are overrepresented in executive and senior management (EEOC, 2015). The National Asian and Pacific American Legal Consortium reported, “although White men make up only 48% of the college-educated workforce, they hold over 90% of the top jobs in the news media, 96% of CEO positions, 86% of law firm partnerships, and 85% of tenured college faculty positions” (American Association for Access, Equity and Diversity, 2015). Growing emphasis on the value and contributions of minorities fosters a sense of exclusion among White males and further weakens support for multicultural diversity initiatives (Plaut, Garnett, Buffardi & Sanchez-Burks, 2011). Studies at a large U.S. healthcare organization sampling of 4,915 responders where 79% were White (modal age 42 – 60 years) demonstrated that, “Whites implicitly perceive multiculturalism as exclusionary and tend not to associate themselves with multiculturalism concepts readily” (Plaut, et al., 2011, p. 347).

Transformational Leadership and Workplace Diversity

“Superior leadership performance− transformational leadership−occurs when leaders broaden and elevate the interests of their employees, when they generate awareness and acceptance of the purposes and mission of the group, and when they stir their employees to look beyond their own self- interest for the good of the group. Transformational leaders achieve these results in one or more ways: They may be charismatic to their followers and thus inspire them; they may meet the emotional needs of each employee; and/or they may intellectually stimulate employees” (Bass, 1990, p. 21).

Transformational leaders, initiate a change process by presenting an ideal, compelling vision. They engage in ongoing conflict resolution and encourage social interactions that foster learning, enthusiasm and commitment to change (Gonzalez, 2010; Nesterkin, 2012). They address resistance by articulating need for change and by answering, “What’s in it for me?” (WIIFM) allowing individuals to personally connect to goals of an initiative. Pragmatically, they assert transactional leadership approaches such as, reward recognition and decision-making latitude (Bass, 1985).

Transformational leaders identify and uncover subtle multidimensional and prevailing ambivalent emotional reactions bringing a much needed psychological competency to change efforts. Developing greater capacity for emotional and cultural intelligence of oneself and others has proven beneficial. Initiatives benefit when transformational leaders remain open and consultative about challenges and encourage those experiencing ambivalence, or have concerns to come forward and voice them (Piderit, 2000) and glean lessons from past initiatives potentially informative to a current one (Ford & Ford, 2009).

Organizational design components and resources such as leadership rank, support staff skill and availability, reporting structures and material and financial resources are essential considerations to project success and can support or jeopardize the work of Chief of Diversity and Inclusion Officers (Leon, 2014). Situating them within the organizational hierarchy by providing sufficient authority, resources and staff to execute diversity strategies optimizes their chances for success. In addition, the frequency with which matters of diversity and inclusion are placed on executive committee agendas have directly influenced the transformational leader’s success (Hopinkah, 2016).

Transformational leaders, as agents of change, raise the performance of others individually and collectively, by empowerment measures, holding accountability for reaching targeted goals and maintaining a focused and collective, integrated approach to the institutionalization of diversity and inclusion (Davalos, 2014). They also understand the influence that planning and implementation of diversity change initiatives have on intergroup relations, take into consideration individual reactions to change and patterns of communication and respond to them in ways that enhance the change effort (Gonzalez, 2010).

Methodology

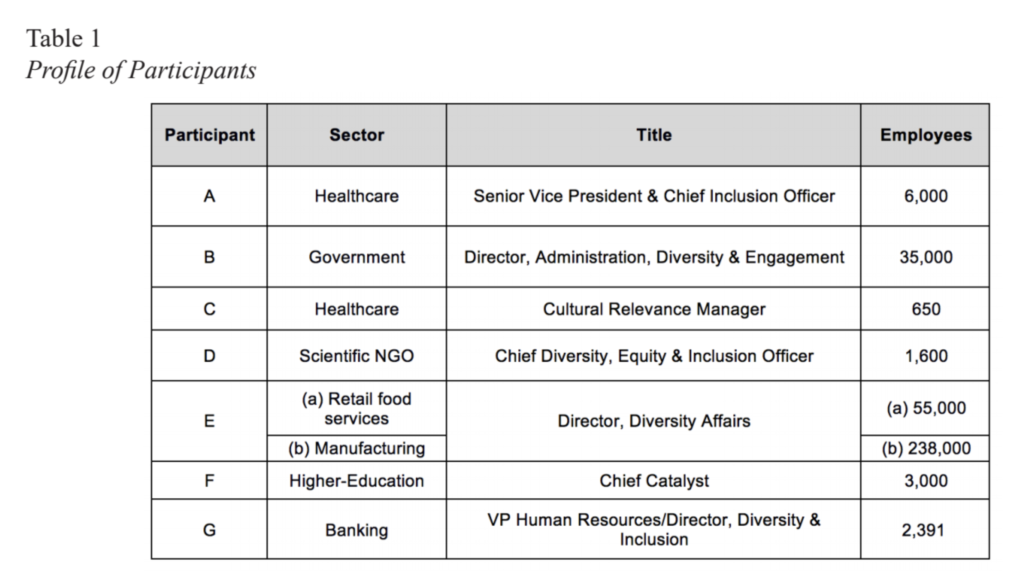

Seven transformational leaders across different organizations, sectors and sizes were recruited as participants through referrals and direct personal contacts based on organization size, rank, years of experience and implementation of diversity and inclusion initiatives (see Table 1). Semi-structured interviews were performed investigating ways that resistance manifests at initiatives and effective strategies that have been deployed to address it. Interviews were followed by a participant feedback session.

Findings

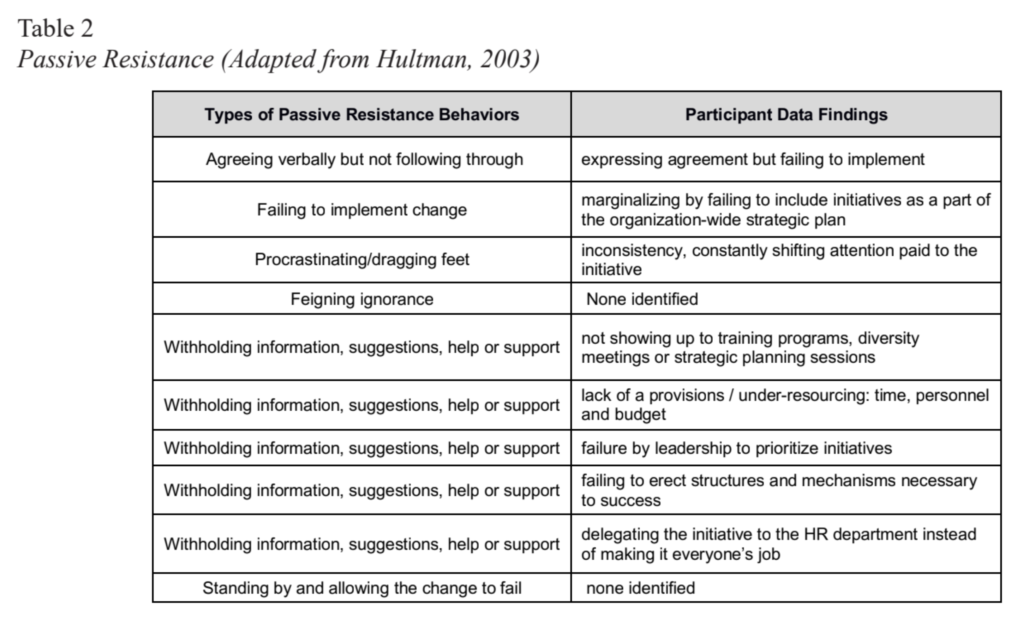

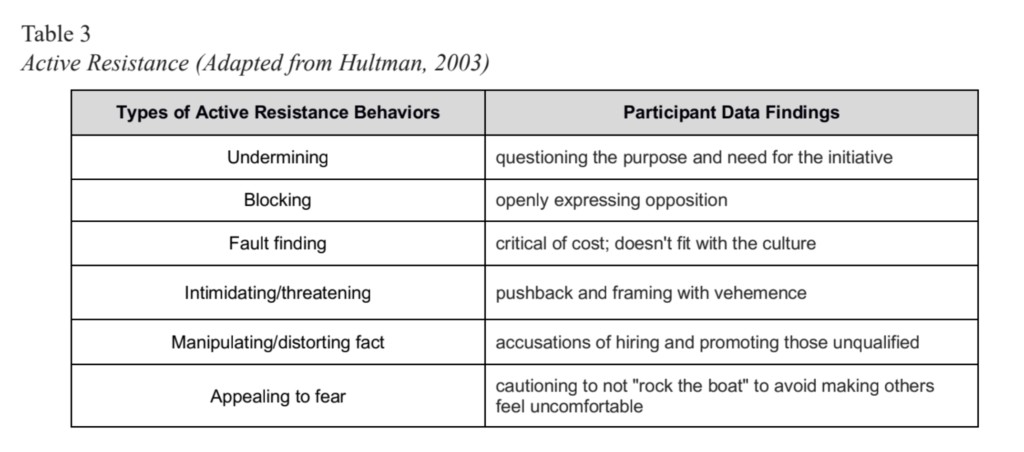

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the types of resistances identified in the interview and feedback session data. They have been sorted using a conceptual framework developed from change management research classifying resistance as passive or active (Hultman, 2003).

Nine passive and six active forms of resistance behaviors were identified. The most prevalent was the passive form withholding information, suggestions, help or support. The ability to identify resistance behaviors enables leaders to educate others and effectively respond to behaviors likely to undermine and impede change success.

Discussion

The participants viewed resistance as an opportunity to clarify assumptions and misconceptions from employees, to understand and empathize with employees’ fears and to further educate them about the importance of the change. They agreed that resistance comes in many different forms, active (visible or overt) and passive (invisible or covert), with active easier to discern and address. Identified sources of fears stemmed from the unknown; of losing privilege and power; and, of being excluded. Resistant passive behaviors included direct opposition and questioning and acquiescing but not wanting to invest the time and other resources to make change succeed. At higher organizational levels dominant resistant behaviors entail lack of prioritization of diversity and inclusion and under-allocation of resources.

Strategies

Strategies identified by the participants to address resistance include: determining the underlying types and sources of fear-based behaviors, inviting dialogue conducive to expressing concerns openly and for educating others about a change and building change competency.

Identifying Underlying Fear

Fear manifests as resistance. Opposition to change increases as employees perceive potential loss of stability (Prediscan and Braduanu, 2012; Williams, 2009; Nesterkin, 2012; Maurer, 1996; Lewin, 1947). Anxiety, nervousness, or unease in anticipation of an uncertain outcome, is an inevitable part of change posing additional resistance to be reckoned with (Nesterkin, 2012; Schein, 2010). Three sources of fear of change arising at times of diversity and inclusion initiatives found in the literature were affirmed by the data: change and the unknown (anxiety); perceived threat of losing privilege and power (injustice); and, of being excluded.

Employees most in opposition perceive having the most to lose in terms of privilege and power (Prediscan & Braduanu, 2012; Nesterkin, 2012). Fear is exacerbated by perceptions of loss of privilege and power related to job, formal position, level of income, earning potential, and formal authority. Perceptions of fairness and equitability, or justice, influences levels of resistance (Smollan, 2006).

Invite Dialogue

Openly sharing information and dialogue (Simoes & Esposito, 2014), participation, and gathering and disseminating feedback are more likely to assure success (Gilley et al., 2012). The data affirms that dialogue decreases resistance. Voluntary engagement such as cross-functional teaming reduces resistance while mandatory approaches activate biases that lead to resistance (Cavaleros, 2002; Kalev, Dobbin & Kelly, 2007; Dobbin & Kalev, 2016).

Educate Others

Transformational leaders address resistance with empathy, facilitate reflection and educate employees to overcome misconceptions (Prieto et al., 2016). Behaviors are symptoms of resistance, root causes, visible manifestations of a person’s mindset (Hultman, 2003). Prevailing racially biased behaviors, or aversive racism, are passive in nature, camouflaged, ambiguous to discern. Often unintentional and unconscious behavioral adaptations they are designed to avert scrutiny and avoid accusations of political incorrectness and unjustness, behaviors deemed socially unacceptable (Dovidio, Gaertner, Kawakami & Hodson, 2002; Prieto et al., 2016).

“We acknowledge that it is far more comfortable and feels safer for those in leadership to maintain the status quo regarding cultural diversity. We further acknowledge that for many leaders who may encounter cultural diversity, may have to work harder to function in that environment; however, organizations that want to remain competitive and sustainable must embrace cultural diversity, not merely tolerate diversity.” (Prieto et al., 2016, p. 45).

Conclusion

Three sources of fear impeding diversity and inclusion initiatives were identified by the data commensurate with prior research reviewed: fear of the unknown (and resulting anxiousness); perceived threat of losing privilege and power (injustice); and, of being excluded. Specific, overt and covert, behaviors and sources of resistance were identified along with strategies transformational leaders use effectively to address resistance.

Limitations and Recommendations

This research was limited to seven interviews thus; a larger sample size utilizing quantitative and mixed-method research approaches would be advantageous. This research makes apparent operative forms of resistance manifest as racial bias, micro-aggression and aversive racism, by nature are covet and is not easily discerned. It is at this crossroad where further investigation could be rich in its findings and useful to diversity and inclusion change practitioners, leaders of organizations and all members of the workforce invested in creating a more advantageous and diverse workforce.

References

Acker, J . (2006). Inequality regimes: Gender, class, and race in organizations. Gender & Society, 20, 441- 464.

Alliance for Board Diversity. (2011). Missing pieces: Women and minorities on Fortune 500 Boards. 2010 Alliance for Board Diversity Census. Retrieved from http:// theabd.org/2012_ABD%20Missing_ Pieces_Final_8_15_13.pdf

American Association for Access, Equity and Diversity (2015). About affirmative action, diversity, and inclusion. Retrieved from https://www.aaaed.org/aaaed/About_ Affirmative_Action__Diversity_and_ Inclusion.asp Bass,

B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18(3), 19-31.

Block, C. J. (2014). The impact of color-blind racial ideology on maintaining racial disparities in organizations. In H. A. Neville, M. E. Gallardo, & D. W. Sue (Eds.), What does it mean to be color blind? Manifestation, dynamics and impact (pp. 263-286). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015). Labor Force Characteristic by race and ethnicity, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/ reports/race-and-ethnicity/2015/pdf/home. pdf

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). Labor Force Characteristic by race and ethnicity, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/ reports/race-and-ethnicity/2016/home.htm

Cavaleros, C., van Vuuren, L.J. and Visser, D. (2002), The effectiveness of a diversity awareness training programme. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 28(3), 50- 61.

Clampitt, P., Williams, M. L. & DeKoch, R.J. (2001). Embracing uncertainty: The executive’s challenge. Journal of Change Management 2(3).

Coetsee, L. (1999). From resistance to commitment. Public Administration Quarterly, 23(2), 204-222. Retrieved from https://fgul.idm. oclc.org/docview/226980583?account id=10868

Davalos, C. D. (2014). The role of chief diversity officers in institutionalizing diversity and inclusion: a multiple case study of three exemplar universities. (Doctoral Dissertations) Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (3581650)

Dent, E. B., & Goldberg, S. G. 1999. Challenging “resistance to change.” Journal of Applied Behavioral Sciences, 35(1): 25-41

Dobbin, F., Kalev, A., & Kelly, E. (2007). Diversity management in corporate America. American Sociological Association, 6, 21- 27.

Dobbin, F., & Kalev, A. (2016, July-August 2016). Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Review, 52-60.

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., Kawakami, K. (2002). Why can we just get alone? Interpersonal biases and interracial distrust. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(2), 88–102.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2015). Retrieved from https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/employment/jobpat- eeo1/

Forbes. (2011). Global diversity and inclusion: Fostering innovation through a diverse workforce. Retrieve from https://images. forbes.com/forbesinsights/StudyPDFs/ Innovation_Through_Diversity.pdf

Ford, J. D., & Ford, L. W. (2009). Decoding resistance to change. Harvard Business Review, 1-4. Retrieved from https://hbr. org/2009/04/decoding-resistance-to-change

Ford, J. D., Ford, L. W., & D’Amelio, A. (2008). Resistance to change: The rest of the story. Academy of Management Review, 33, 362- 377.

Garr, S. (2014). New research reveals Diversity & Inclusion well-intentioned, but lacking, Bersin by Deloitte. Retrieved from www. bersin.com/blog/post/New-research- reveals-Diversity–Inclusion-efforts-well- intentioned2c-but- lacking.aspx

Gilley A., Thomson J. H., Gilley J. W. (2012) Leaders and Change: Attend to the Uniqueness of Individuals. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 69-83.

Gonzalez, J. A. (2010). Diversity change in organizations: A systemic, multilevel and nonlinear process. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 46 , 197-219.

Ghorashi,H.&Sabelis,I.(2013),Jugglingdifference and sameness: rethinking strategies for diversity in organizations. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 29(1), 78-86.

Herring, Cedric (2009). Does diversity pay? Race, gender and the business case for diversity. American Sociological Review, 74(2), 208- 224.

Holck, L. (2016). Putting diversity to work: An empirical analysis of how change efforts targeting organizational inequity failed. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 35(4), 296-307

Hopinkah, K. H. (2014). Diversity and inclusion leadership: A correlative study of authentic and transformational leadership styles of CEOs and their relationships to gender diversity and organizational inclusiveness in Fortune 1000 companies. (Doctoral Dissertations) Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations (10257425).

Hultman, K. E. (2003). Managing resistance to change. Encyclopedia of Information Systems, 3, 693-705.

Jackson, S. E., & Joshi, A. (2011). Work team diversity. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (1st ed., pp. 651–686). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Jansen, W. S., Otten, S., & van der Zee, K. I. (2015). Being part of diversity: The effects of an all- inclusive multicultural diversity approach on majority members’ perceived inclusion and support for organizational diversity efforts. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 18(6), 817-832.

Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity and inclusion policies. American Sociological Review, 71, 589-617.

Kalev, A. (2009). Cracking the glass cages? Restructuring and ascriptive inequality at work. American Journal of Sociology, 114(6), 1591–1643.

Leon, R. A. (2014). The chief diversity officer: An examination of CDIO models and strategies. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(2), 77-91.

Lewin, K. (1947). Quasi-stationary social equilibria and the problem of permanent change. In K. Benne and B. Muntyan (Eds.) Human relations in curriculum change (39-44). New York, NY: University of Illinois the Dryden Press.

LucasJ.W. & BaxterA.R.(2012). Power,Influence, and Diversity in Organizations. ANNALS, AAPSS, 639, 49 – 69

Maurer, R. (1996). Using resistance to build support for change. Journal for Quality and Participation, 56-63.

McKinsey. (2015). Why diversity matters. Retrieved from: https://www.mckinsey.com/business- functions/organization/our-insights/why- diversity-matters

Merron, K. 1993. Let’s bury the term resistance. Organizational Development Journal, 11(4),77-86.

Monaghan, C. H. (2010). Working against the grain: white privilege in human resource development. Wiley Periodicals, Inc., 125, 55-65.

Mor Barak, M. E. (2015) Inclusion is the key to diversity management, but what is inclusion?, Human service organizations, Management, Leadership & Governance, 39(2), 83-88.

Muo, I. (2014). The other side of change resistance. International Review of Management and Business Research, 3, 96-112.

Nesterkin, D. A. (2012). Organizational change and psychological reactance. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 26, 573-594. Retrieved from http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/ pdfplus/10.1108/09534811311328588

Oreg, S. (2003). Resistance to change: Developing an individual differences measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 680-693.

Piderit, S. K. (2000). Rethinking resistance and recognizing ambivalence: a multidimensional view of attitudes toward an organizational change. Academy of Management Review, 25, 783-793.

Plaut,VC;Garnett,FG;Buffardi,LE;Sanchez-Burks, J. (2011). “What about me?” Perceptions of exclusion and whites’ reactions to multiculturalism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,101(2),337-353.

Powell, G., & Butterfield, D. A. (1997). Effect of race on promotions to top management in a federal department. Academy of Management Review, 40, 112-128.

Prediscan, M., & Braduanu, D. (2012). Change agent: a force generating resistance to change within and organization? AUDCE, 8, 5-12.

Prieto, L. C.; Norman, M. V.; Phipps, S. T. A. & Chenault, E. B. S. (2016). Tackling micro- aggressions in organizations: A broken windows approach. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics; Lighthouse Point, 13(3), 36-49.

Schein, E. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Simoes, P .M. M. & Esposito, M. (2014) Improving change management: how communication nature influences resistance to change. Journal of Management Development, 33(4), 324-341.

Smollan, R. K. (2006) Minds, hearts and deeds: Cognitive, affective and behavioural responses to change. Journal of Change Management, 6(2), 143- 158. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1080/14697010600725400

Stephanopoulos, G. & Edley, Jr., (1995). Affirmative action: history and rationale: Clinton administration’s affirmative action review: Report to the President 1995. Retrieved from https://clintonwhitehouse2.archives. gov/WH/EOP/OP/html/aa/aa-index.html

Williams, V. E. (2009). Organizational change and leadership within a small nonprofit organization: A qualitative study of servant -leadership and resistance to change. (Doctoral Dissertations) Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (3387854)

Williams, D. A., & Wade-Golden, K. (2013). The chief diversity officer: Strategy, structure, and change management. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Wingfield, A. H., & Alston, R. S. (2014). Maintaining hierarchies in predominantly White organizations: A theory of racial tasks. American Behavioral Scientist, 58, 274-287.

Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Read more Posts

Unlock Resilience And Agility As A Purpose-Driven, Evolutionary Leader

“By understanding your organization’s current center of gravity, you can establish a baseline from which to evolve as a leader.”

Inclusive Leadership Cultivates Positive Employee Engagement

“Strong leaders that cultivate employee engagement are sensitive to the full humanity of their employees”